"Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth."

- Cathy Shen

- 5 days ago

- 8 min read

Such a shocking statement naturally comes from an artist who defies convention. He is called Pablo Picasso.

I recently saw the special exhibition "Extraordinary Picasso" at the Pudong Art Museum. One exhibition hall was particularly interesting, as it featured Picasso's variations on The Luncheon on the Grass, which was created in the 1960s. According to reports, this Cubist pioneer created over 27 oil paintings and numerous sketches inspired by The Luncheon on the Grass. This prompted an intriguing question for me: as two masters separated by 100 years who were both "ahead of their time" throughout their careers, what inspired Manet and Picasso's "subversion"? Could there be "formal similarities" or even "spiritual resonance" between The Luncheon on the Grass, Cubism, and works from other periods or regions?

The Strange Light, Shadow, and Composition in The Luncheon on the Grass

Édouard Manet (1832-1883) was a French painter hailed as the "Father of Modernism." His works bridged the gap between the traditional academic style and Impressionism. His masterpiece The Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, 1863) caused an uproar for breaking the mythological narrative tradition of classical painting. Rejected by the official Salon of 1863, it created a sensation at the "Salon des Refusés," becoming a milestone in art history that challenged tradition and ushered in modern art.

"A lonely prophet who changed the entire course of art history with a 'failed' painting." This is how Picasso evaluated Manet and his epoch-making masterpiece.

To understand this painting's "heresy," we must first understand what "correctness" looked like in the 1863 academic style and then see what Manet shattered. The official French Salon in the mid-19th century was controlled by reviewers from the École des Beaux-Arts, who followed a set of golden rules: perfect perspective, subtle light-shadow transitions, hidden brushstrokes, idealized human bodies, and clear narratives. By these "correct" standards, The Luncheon on the Grass was indeed full of "bugs."

I. Subversion in Composition

1. The "Failure" of Perspective

The academic style required a strict focal perspective with clear spatial layers—near objects large, distant objects small. But Manet did this: the woman in the background is disproportionately large, as if "pasted" above the foreground figures; the middle ground is almost absent, and the space is "flattened"; the grass appears to rise almost vertically like a backdrop.

The viewer feels confused—this is not a space you can "walk into," but an obvious stage set.

2. The "Absurdity" of Character Relationships

The academic style required clear narrative interaction between figures—eye contact, gesture responses, and emotional connections. But Manet painted this: two well-dressed gentlemen converse, but their postures are stiff, like posed photographs; the nude woman stares directly at the viewer with no interaction with the men beside her; the woman in the background bends over in the water, disconnected from the foreground scene; and the foreground still life (clothing, food basket) is scattered casually, lacking the careful arrangement of traditional still life painting.

This is not a "story" but a group of unrelated figures collaged together. The viewer cannot "read" this painting using traditional narrative logic.

II. Revolution in Light and Shadow Treatment

This is Manet's most technically subversive aspect and what academic painters found most intolerable.

1. Eliminating "Mid-tones"

Academic light-shadow requirements: from brightest to darkest, there should be countless subtle gray transitions. This gradation creates volume and a three-dimensional illusion, with skin appearing silky smooth and the boundary between light and dark almost invisible. Manet's approach: highlights and shadows are directly adjacent, omitting transitional tones; the three-dimensional quality of figures is greatly reduced, making them look like paper cutouts pasted on the background.

Critics at the time mocked, "This woman has no bones, no muscles, only skin."

2. "Flash Photography-style" Frontal Lighting

Academic lighting typically used 45-degree sidelight (Rembrandt lighting) to create rich contrast and drama. But Manet let the light come almost completely from the front, compressing shadows to a minimum, without traditional shadow boundaries to sculpt volume.

This "flat" lighting later became known as "Manet-style lighting," as if predicting the effect of photographic flash half a century later. It refused to create a depth illusion, emphasizing the flatness of the picture plane.

3. Contradictory Light Sources

The academic style required unified, believable light sources within the picture. Manet's "errors": the foreground figures appear completed under soft studio light, while the background woman bathes in outdoor natural light—two types of lighting that cannot coexist in the same physical space.

This further broke spatial unity and reinforced the "collage" effect.

Beyond composition and lighting, The Luncheon on the Grass also "remixed" figures from Raphael's The Judgment of Paris and Titian's Pastoral Concert, replacing them with Parisian gentlemen in contemporary clothing and naked modern women. It also interpreted the scene with "rough" brushwork and colors: loose, sketch-like strokes directly juxtaposing different color blocks on the canvas with visible brushwork. This technique directly inspired the later Impressionists.

Some summarize Manet's approach as influenced by "Ukiyo-e" prints of the time, containing elements of Eastern "scattered perspective." But I believe even if there are some "formal similarities," it was not Manet's intention. Eastern painting emphasizes "shifting scenes with each step," arranging objects observed from different angles on the same canvas to achieve overall harmonious beauty. So in a traditional Chinese landscape painting, you can see mountains viewed from below and rivers viewed from above. Of course, Chinese painting also uses color depth, brush weight, and line detail to convey spatial sense, preventing viewer confusion. This technique is more like a painter's record while wandering through landscapes, not a view seen simultaneously from the same angle. Traditional Chinese landscape painting pursues a kind of "realm" (境)—both "artistic conception" (意境) and "state of mind" (心境). The core of this "realm" lies in the fusion of "heart" and "object," not the objective reproduction of nature. It conveys a spiritual state and life attitude.

Looking at The Luncheon on the Grass, can you find this "realm"? Can you feel "spiritual resonance" between the two painting traditions? My answer is no. Although compared to academic classics, this painting's space is indeed "flattened," careful observation of objects like the boat still reveals basic "focal perspective"—this can hardly even be called "formally similar" to Chinese painting. And compared to perspective composition, this painting's most obvious feature is its breakthrough in light and shadow treatment. I believe Manet's rebellion was less a technical innovation than an attitudinal revolution—he refused to follow "tradition" for tradition's sake and refused to follow "rules" for rules' sake. He wanted to see with his own eyes and speak with his own brush. This is why posterity called him the "Father of Modern Painting."

Cubism, Scattered Perspective, and Ancient Egyptian Painting

Having discussed Manet, let's talk about his "fan," Picasso, and his Cubism.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) was a Spanish artist recognized as one of the most influential masters of the 20th century. His creative styles spanned the Blue Period, Rose Period, Cubism, Surrealism, and other phases. Cubism was co-founded by Picasso and Georges Braque around 1907. Its core concept was to break the single viewpoint, decomposing objects into geometric shapes and presenting them from multiple angles simultaneously on a two-dimensional surface. Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) is considered the founding work of Cubism. This movement completely overturned the perspective laws since the Renaissance, profoundly influencing subsequent abstract art, architectural design, and all modern visual culture.

One of the most important contemporary British artists, David Hockney, is fascinated by the scattered perspective of Chinese painting. He studied the spatial expression methods of ancient Chinese scroll paintings and combined them with Picasso's Cubist concepts for new creative practices. Hockney believes Western focal perspective is a "Cyclops" way of seeing, while Chinese painting's "roaming view" is closer to how human eyes actually see—coinciding with Cubism's pursuit.

On the surface, both Cubism and Chinese scattered perspective "break the single viewpoint," but deeper examination reveals their temporal-spatial treatment and spiritual cores are completely different.

1. Different Philosophical Roots

Cubism: Originated from modernist cognitive anxiety—"Can we really see the essence of things? " Picasso and Braque tried to present the front, back, left, and right of objects simultaneously to reveal a more complete "reality."

Chinese scattered perspective: Originated from the Taoist spirit of "wandering"—not to see clearly, but to let the soul roam through mountains and waters. It pursues an experience of "can walk through, can gaze upon, can roam in, can dwell in."

2. Different Concepts of Time

Cubism: It is simultaneity—compressing different angles into the same instant, a freezing and layering of time.

Chinese painting: Is diachronic—as the scroll unfolds, the viewer seems to walk through the painting; time is flowing and continuous (like Along the River During the Qingming Festival). The Deji Art Museum in Nanjing's digital painting of Jinling uses AI technology to place visitors' chosen characters into the painting scene, with audiences wearing wristbands synchronized with figures in the painting, as if traveling through Song Dynasty Jinling City.

3. Different Spatial Treatment

Cubism: Space is fragmented and deconstructed; objects are broken apart and reassembled with analytical and rational implications.

Chinese painting: Space is continuous and flowing; mountains overlap and paths turn—it's a pathway you can walk into.

4. Different Emotional Tones

Cubism: Carries tension and intellectuality—it challenges visual habits; viewers must "work hard to see."

Chinese painting: Pursues tranquility and poetry—it invites viewers to "relax and roam," ultimately achieving spiritual solace.

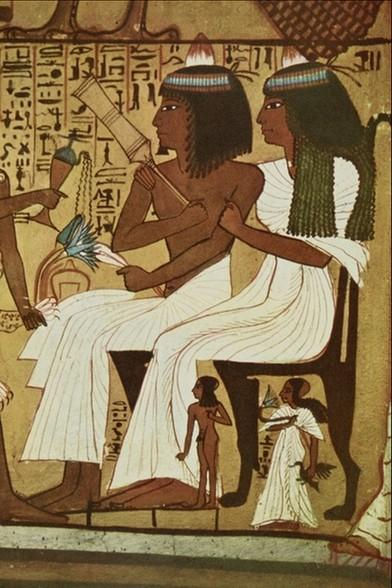

Speaking of this, let's look at the "formal similarities" between ancient Egyptian painting and Cubism.

Ancient Egyptians presented each body part from its "most characteristic" angle: the head in profile shows the clearest outline, the eye is most complete from the front, and shoulders are widest from the front. Scholars call this "aspective" (conceptual perspective), contrasting with optically based "perspective." Cubism similarly rejected the single viewpoint; Picasso compressed frontal, profile, and three-quarter angles simultaneously onto one face in works like Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

Moreover, neither pursued the "reality" seen from one angle at one instant, but a complete presentation transcending time and space: Egyptian art wanted to present what a person "essentially is," not "what they look like at this moment"; Cubism wanted to present all information about an object "existing as a whole in space."

Of course, these two art forms separated by thousands of years are certainly not the same thing. Their creative intentions differ: Egyptian art had to be clear, complete, and recognizable, not beautiful or "lifelike." A frontal eye is more "complete" than a profile eye, so even with the head in profile, the eye was drawn frontally. Cubism thought traditional perspective paintings only presented one "slice" of an object—a visual lie. Cubism tried to present multiple sides of three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional plane to reveal a more complete perceptual reality.

Conclusion

Returning to the title of this essay, this is one of Picasso's most profound quotes. On the surface, it seems paradoxical—how can a "lie" reveal "truth"? But his meaning is: art is not a copy of reality but a transformation and distillation. It is precisely through this "unreality" that we can see the essence hidden in reality. The Luncheon on the Grass presents an "unreal" scene precisely to expose the hypocrisy of the academic "reality" of its time; Cubism "distorts" appearances but presents a more complete existence.

Chinese painting's scattered perspective is more like a "lie" that has lasted thousands of years—it never tried to "look real." But it is precisely this lie that lets us see the truth obscured by focal perspective: our relationship with the world is far richer, more fluid, and more intimate than what a window, a lens, or a single instant can capture. David Hockney said, "Photography and Renaissance perspective both turn us into spectators of the world, but Chinese painting makes us participants in the world."

Comments