Starting from the Stage Design Controversy at Jolin Tsai's Concert

- Cathy Shen

- Jan 13

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 14

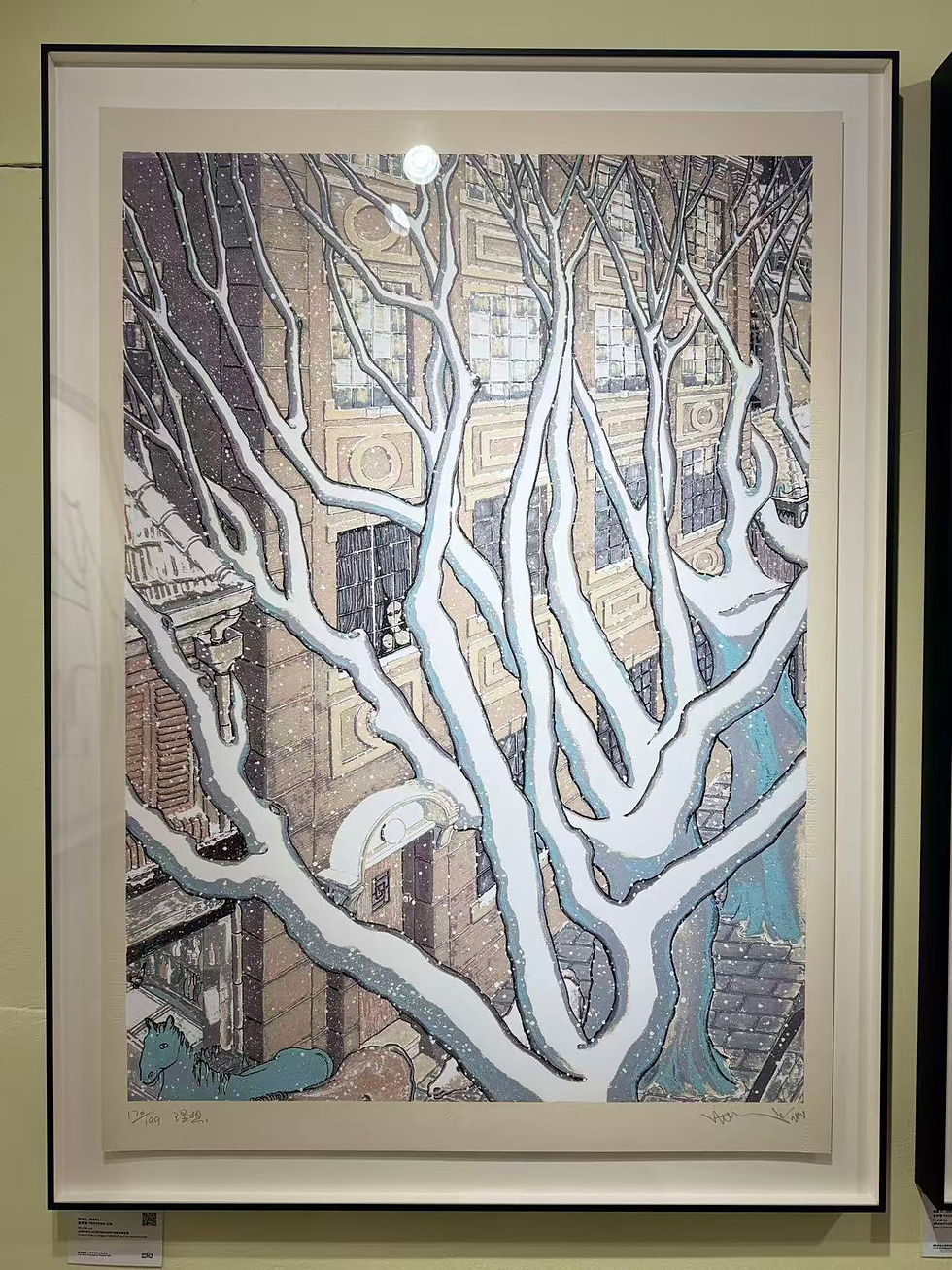

The premiere of Jolin Tsai's PLEASURE World Tour was held at the Taipei Dome from December 30, 2025, to January 1, 2026, concluding with enormous success. The tour's stage design featured mythical beasts such as a celebratory bull, a rainbow-winged Pegasus, and a golden pig of greed, complemented by a purgatorial forest of swords and a seven-story-tall "Lady of Pleasure" installation—all combining to create a fantastical world. However, this avant-garde stage design immediately sparked controversy, with some netizens accusing Jolin Tsai of using her concert to promote cult ideology. The organizers subsequently issued a clarification, explaining that the stage design was inspired by The Garden of Earthly Delights, a masterpiece by the 16th-century Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch, and had absolutely nothing to do with any cult.

As a result, the public unexpectedly thrust my favorite Northern Renaissance painter and his masterpiece into the spotlight.

Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–August 9, 1516) was one of the most original and enigmatic painters of the Dutch Renaissance. Though Bosch never ventured far from his hometown, he created works that astonished all of Europe. Unlike his contemporaries who pursued realism, Bosch developed a highly distinctive visual language filled with bizarre creatures, grotesque scenes, and profound symbolism. Some even consider Bosch the forefather of modern Surrealism. His works are said to reveal "profound insights into human desires and our deepest fears."

The Garden of Earthly Delights is Bosch's most celebrated masterpiece, currently housed in the Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain. This triptych, created approximately between 1490 and 1510, is renowned for its fantastically wild imagery and intricate symbolic system. The entire work is actually an altarpiece painted on wooden panels. When fully opened, it measures approximately 3.9 meters wide and 2.2 meters tall, comprising three panels that present a complete narrative from left to right: the left panel depicts the Garden of Eden, showing God, Adam, and Eve in scenes of creation and innocence; the central panel portrays the Garden of Earthly Delights, where numerous nude figures indulge in sensory pleasures; and the right panel presents Hell, depicting sinners suffering various bizarre torments. From innocence to corruption to punishment, from creation to the end of days, Bosch condensed the entire history of humanity into these three panels. The artist wished to warn viewers that the pleasures of the flesh are fleeting illusions, and that only the salvation of the soul is eternal.

Hieronymus Bosch's paintings constitute a unique interpretive puzzle in art history. For five hundred years, scholars have approached his works from vastly different perspectives—religious orthodoxy, heretical thought, alchemy, psychopathology, and even as a precursor to Surrealism—yet have never reached consensus. This "cacophony of interpretations" itself reveals the complexity of Bosch's art: he created a visual language that was both rooted in medieval tradition and transcendent of his era's limitations. The current orthodox interpretation of Bosch and his Garden of Earthly Delights is summarized in three points:

Bosch was a devout Catholic, and his works can be fully explained within the framework of orthodox faith.

Those seemingly transgressive images are actually satires and warnings against sin, not celebrations of it;

The central panel depicts humanity's madness in a state of corruption, not any idealized community.

In fact, The Garden of Earthly Delights contains numerous metaphors and symbols. For example, in the right panel, Adam in Hell appears to be coerced into signing some sort of agreement. Some researchers believe that the painting satirizes the Church's practice of selling "indulgences" to the public at that time—essentially paying money to atone for sins.

The abundant animal imagery in Bosch's works was not conjured from thin air but is deeply rooted in the iconographic tradition of medieval bestiaries. These texts combined descriptions of animals with Christian moral teachings, assigning specific symbolic meanings to each creature. What makes Bosch unique is that he did not simply copy these traditional symbols; instead, he recombined, transformed, and hybridized them to create unprecedented visual images. For instance, his half-human, half-beast, half-plant, half-mechanical hybrid creatures represent a radical reconstruction of traditional allegorical imagery. Bosch also did something revolutionary: he elevated these formerly marginal "grotesque" figures to become the protagonists of his paintings. In traditional religious art, monsters were merely supporting characters in saints' narratives; in Bosch's works, however, these monsters occupy center stage, equally important as—if not more striking than—the human figures. This "centralization of the marginal" constitutes one of the most subversive characteristics of Bosch's art.

From this perspective, if Jolin Tsai's concert stage design was indeed inspired by The Garden of Earthly Delights, then the misunderstanding she faced is somewhat unfair. I am willing to applaud her bravery in recreating a classic. Concert staging must provide visual impact to the audience, just as we can't help but exclaim 'wow' when we first open The Garden of Earthly Delights. However, when referencing a grotesque artwork like The Garden of Earthly Delights—one laden with complex symbolism and obscure metaphors—it may be worth giving extra consideration to audience receptiveness.

Comments